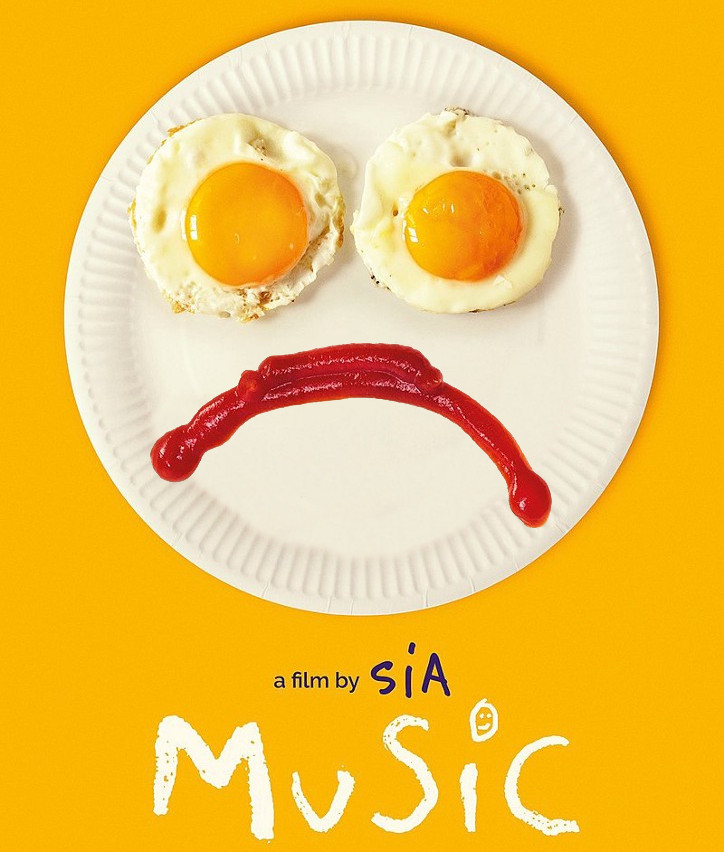

This blog usually covers topics related to autism or topics related to neurodivergence. As such, my knowledge of the creative arts aren’t exactly necessary for this type of work. However, I am more than willing to make an exception or two should the need arise that requires perspective from a neurodivergent creative; this atrocity masquerading as cinematographic art is one such exception. I am of course writing about pop singer Sia’s debut ‘film’ Music.

Do not get me wrong. Portraying both non-verbal autism and having the autistic character be female (when most representations are male) are worthy concepts for a movie. However, this extremely patronizing and clichéd assault on cinematography was not the way to do it.

If you somehow do not take my word or the words of the several autistic YouTubers who commented on it, Rotten Tomatoes has given the film a 10% rating with an audience score of 15%. To put that into perspective, the film Cats got a 19% critic score and Batman and Robin got an 11% score on the same website. Getting a lower score than two of the worst films critiqued on that website is a horrid achievement in and of itself, but that is, thankfully, its only achievement.

This is not yet even getting into the controversies when it comes to the film’s creation, casting, editing, and Sia’s response to criticisms.

To begin, the film’s trailer was panned from the start over the reveal that Sia’s “muse”, neurotypical Maddie Ziegler, would be playing the nonverbal Music. Naturally, autists everywhere were outraged. One, Sia’s decision took away a casting opportunity from an actress who’s actually autistic. Two, Ziegler was uncomfortable in playing this role to the point that the poor girl had sobbing breakdowns on set over fear that people would hate her for this movie. Three, Ziegler having no say in this adds even further fuel to the abusive and manipulative implications of her relationship with Sia. And four, despite Sia saying that she unsuccessfully tried the role with one nonverbal actress and that she cast Ziegler “out of compassion”, reports and interviews from a few years prior state Sia developed the project with Ziegler in mind and merely lied about the nonverbal actress to save face. Not helping was the fact that the Australian idol had supposedly been researching autism for three years prior to production, yet the results of her ‘passion project’ show that either Sia is extremely ignorant and surrounded by enablers or that Sia cannot do her homework to save her life. Or in this case, her career.

The criticisms escalated once scenes were shown of the characters using prone restraints on Music to calm her during a meltdown. The one introducing the use of said restraints even refers to it as “crushing” Music with “love”. Being forcibly immobilized is incredibly traumatic to an autistic person both on a mental and physical level. The act is also incredibly dangerous as it can suffocate and kill the person being restrained; autistic children have died in the past because of this technique. I myself have witnessed firsthand prone restraints being used on distraught young teenagers. It does not calm them down or deescalate the situation. The criticisms reached a point that Sia stated that the scenes showing the use of restraints would be removed upon release and there would be a disclaimer advising against their use. The US release is unedited.

The final nail in Music’s pre-release coffin was an escalation of Sia’s responses to these criticisms. The most telling of these were her Twitter responses to the several autistic actors who rightly called her out on the fact that Sia put no effort into including anyone who was actually autistic in the planning of the film or made an effort to find an autistic actor. Sia’s responses range from “Maybe you’re just a bad actor” to profanity usage claiming that they have no idea what they are saying because they have not seen the movie.

Yet the ‘film’ was somehow nominated for 2 Golden Globes despite being so ill-received! This blogger speculates that the powerful devices called money and notoriety were at play here. Being the directorial debut of an incredibly popular pop star as well as said pop star’s financial influence were most likely the reasons why the movie was considered in the first place, sad to say.

Music’s premise is one that continues to reinforce harmful stereotypies about people with disabilities. The kind of movies that prop up the disabled as if they are some kind of inspirational paragon for going through life with their handicaps (“Oh, they’re so brave!”). Usually these paragons who can do no wrong are handed off to sullen family members who will slowly become happier over the movie as their disabled burdens touch everyone around them with their magical pixie dust brand of oblivious pluck (“I thought I was raising Music, but it was really Music raising me!”). The fact that these types of movies and other mediums are made primarily for Oscar bait and nothing else is downright insulting for people like myself who are usually the ones being depicted in them. The insincerity and artificiality in this one is sickening.

Music herself is portrayed as blissfully unaware of everything around her. We almost never find out anything about Music aside from her special interest – dogs – and the sequences that, supposedly, only take place in her head. However, the latter is rendered moot by her sister and the neighbor getting sequences of their own later. We never really learn anything else about her. Aside from her autistic traits, we don’t know what she likes, what she dislikes, or even how she feels about the new situation she’s in. Or any, for that matter. The movie claims that Music understands the situation she’s in and can comprehend what goes on around her, but every single scene has Music staring off into space with her mouth open in a dopey wide grin, doing something incredibly childish even by child standards, ‘attempting’ to speak like the Hulk (“Make you eggs!”), and flailing around so much that it looks like she is having a series of epileptic seizures. Sadly, this is likely how Sia sees autistic people in general – not as actual people with hard lives in a world that doesn’t understand them, but as props. Things to pity and nothing more. We only exist for normal people to feel better about themselves.

That’s not to say that the title character is the only problem with this movie, oh no. This movie is rotten to the core with its bad writing and clichés. As I mentioned earlier there continues to be a continuation of harmful stereotypes in this film and a disturbing parallel between Simple Jack (a parody film-within-a-film made 10 years ago on this very topic) and oh stars, does it show. The premise of the film is as predictable as it is insulting: the grandmother and sole caretaker of our title character dies and custody is given to the real main character of the film – unemployed recovering drug addict/dealer and half-sister Kazu, who is less than thrilled with her new burden. Over the course of the movie, Kazu tries, unsuccessfully, to pass off Music to anyone willing to put up with her, including dropping her off at an adoption agency. Eventually, she learns to ‘accept’ Music as Music changes the lives of everyone around her. Blech.

In addition, there is a boy, Felix, whose side plotline interrupts the film several times and never ties into the main story. Felix is also autistic and lives in an abusive family. It ends with his father killing him during a domestic dispute. That’s it. We never know what happened to his parents. His father never receives any sort of karmic justice. The side plot just ends on that grim note. It’s sickening.

As I’ve seen a couple others more familiar with her songs note, Sia’s view of the world is extremely idealized. Unfortunately, this transferred over to the film in the worst possible way. By idealizing Music’s experiences, Sia failed to capture the fact that being autistic is a struggle. Sia is of the mindset that, as long as Kazu accepts Music in her life, everything will be okay. Which is not true. The marginalized struggle because people will NOT accept them. Music would NOT be loved by everyone around her. Everyone would NOT treat Music with respect and, thus, make her life ‘better’. In the real world, Music would be given strange looks on her daily walks. She’d be bullied for acting out, even by her own family. Music would have the cops called on her and possibly face charges for her meltdowns.

Sia, who need I remind you wrote, directed, and produced this ‘film’, claims it is a love letter to autistic people and the caregivers of the disabled overall, but I can see right through her. Sia does not really care about those affected at all, only what our struggles can do for her career. A reviewer mentioned something about her which I agree with. I don’t think Sia wants people who are different to actually succeed. Sia wants to accept us in our failures and not our successes. She only sees us for what we are and not what we can be. We are merely tools for other people to feel better about themselves. We are things to be used for Oscar bait.

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions, but not Sia’s. Hers is merely a glorified vanity project that dares to pretend it is something more. To call Sia’s ‘movie’ tone deaf barely covers just how awful it is to all parties involved. In short, Sia’s vain off-key debut is best left on mute. Forever.